When it comes to fairness, there’s something for everyone. Unfortunately, it’s rarely the same thing. The concept of fairness is a shape-shifter. How do we understand “Unfair!” when it is trumpeted by a politician to bemoan treatment during the investigation of massive, international white-collar crime, and also employed by exhausted students wishing to discretely use a restroom that matches their presenting gender? And are these sorts of unfairness the same as the unfairness protested at city halls around the nation when it is discovered that schools in some districts have been allowed to flounder underfunded, while others have been better endowed?

Philosophers and psychologists have long traced the many forms of fairness, and advances in the social sciences and neuroscience have enabled us to better understand the implications of these distinctions. One interesting feature that becomes vivid when observations across disciplines are taken together is that the principles guiding people’s fairness judgements compete. In a series of studies aimed at understanding fairness controversies I conducted with psychologist Liane Young from Boston College, we explored three commonly observed fairness principles: reciprocity, charity, and impartiality.

Reciprocity reflects the belief that it’s fair to allocate more to the person who allocated to you. Charity, or needs-based allocation, is guided by a belief that it’s fair to allocate to “level the playing field”. Impartiality reflects the belief that allocations should be uninfluenced by people’s unique circumstances. As such, impartiality is “person-blind”. Reciprocity and charity, by contrast, are both “person-based”, taking into account the unique deeds and needs of potential recipients.

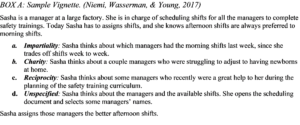

In our studies, we considered group scenarios in which numerous people had an interest in a resource, and one person had the capacity to allocate that resource. We presented research participants with vignettes in which people in everyday roles (e.g. teachers, coaches, managers) allocated something that several people wanted (e.g., time with a favoured instrument, desired shifts at work). We varied the allocators’ method according to the different fairness types: reciprocity, charity, impartiality, and unspecified (the control condition). We were interested in what people thought motivated these differing kinds of allocations, how fair and moral they considered them to be, and whether individual dispositional differences in the participants contributed to differences in assessments. As reported in Social Justice Research in 2017, Young and I found that differing modes of allocation were linked to differences in perceived motivations, normative judgements, and participants’ own dispositions.

For example, consider a factory manager tasked with allocating shifts. She might allocate based on impartiality, by allocating to whoever is next on the schedule. She might decide to allocate based on need (charity) by giving the desirable shifts to employees struggling to adjust to having newborns at home. She might allocate based on reciprocity by giving the desirable shifts to employees who recently helped her plan a training course. Considerations of reciprocity and charity are personal considerations, based on individuals’ past deeds and current needs, respectively. By contrast, to be impartial, one allocates consistently across individuals, typically by using a rule, such as a set of impersonal standardised criteria. (See Box A for a sample vignette and the four conditions.)

Our first, and most important, finding was that participants rated the impartiality vignettes as, by far, the most fair. If there is a go-to, prototypical fairness, it is impartiality – as Rawls would tell you, supported by the work of many other philosophers and psychologists. Intriguingly, Alex Shaw of The University of Chicago’s Psychology Department and his colleagues recently showed that people disdain creating partiality so much, they throw excess resources they’re tasked with distributing into the rubbish to maintain equality.

Individual differences also matter. Although people broadly agreed about the fairness of impartiality, some people also folded other considerations into their idea of fairness. Participants’ individual difference variables were linked to the likelihood that they perceived fairness to also include reciprocity or charity. On average, participants considered reciprocity to be the least fair, and the least morally praiseworthy allocation method. Yet people higher in Machiavellianism considered reciprocity to be significantly more fair than people lower in this variable. Machiavellianism, a well-studied individual difference variable, involves a desire for status and control, in which inequality is just fine: the world is a place where some people are superior to others, and Machiavellian people are committed to being in the superior class. Highly Machiavellian people engage in morally questionable means to pursue these personal goals, and deceptively build secret relational ties as an important wayto get ahead. Reciprocity is the basis of many dyadic relationships; returning favours is polite and expected social behaviour. But outside of a friendship, where multiple people have rights to access or bid for a resource, reciprocity builds relational ties that push out some people to benefit a select few. Thus, reciprocal construals of fairness can be a tool that enables individuals high in Machiavellianism to further their goals by prioritising social relationships over impartiality.

While some see fairness in the impartial blindfold and others in eyes-on-the-prize tit-for-tat reciprocity, for others still, fairness follows the needy. On average, our participants considered charity less fair than impartiality. However, they did consider it equally morally praiseworthy. The potential for conflict here is easily seen. As we know from debates around programs involving allocating to people in need, it’s possible for charitable allocations to be viewed as good but not maximally fair. In these cases, a lack of impartiality is spotlighted and the fact that people in the most need are “targeted for special treatment” is presented as a procedural failing. Resulting skirmishes lead to resources being squandered as principles are put before persons.

How to escape this conundrum? Some of our participants appeared to have the psychological equipment: those high in empathic concern. This dispositional feature, measured by the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, reflects a tendency for concern for those who are worse off. People high in empathic concern were more likely to subsume charity, or allocating to the neediest, within their definition of fairness.

The participants who considered reciprocity and charity to be fair could not seem more different:the Machiavellians and the Empaths, respectively. Yet strikingly, when one examines the data on how participants perceived the allocators in the vignettes to be motivated, and the neural processing patterns when participants’ morally judged the allocators, reciprocity and charity begin to look very alike.

The allocators in the reciprocity and charity vignettes were judged as significantly more motivated by the unique states of individuals, whereas the allocators in the impartiality vignettes were judged as more motivated by the overall state of the group. Reciprocity and charity allocators were judged as significantly more motivated by their own emotion, and less by standard procedures, compared to impartial allocators.

In ratings of the difficulty of making a moral judgement (how hard participants thought it was to judge the allocator as “doing the right thing”), both reciprocity and charity were considered more difficult to judge as “doing the right thing”, compared to impartiality. Reciprocity stood apart from charity on only one dimension: it was considered significantly more motivated by the allocator’s personal goals. These ratings helped shed light on what features are important to most people’s sense of fairness – they tend to like their fairness group-oriented, unemotional, impersonal.

As we prepared for scanning, we wondered if, because people considered reciprocity and charity more motivated by the unique states of individuals and emotion, we might see enhanced neural activity in brain regions that support thinking about the contents of other people’s minds for both reciprocity and charity, relative to impartiality. On the other hand, what distinguished between reciprocity and charity was a difference in motivation by personal goals. Work in social neuroscience demonstrates that theory of mind brain regions code for mental states like goal planning. We might expect, therefore, to see reciprocity and charity diverge in theory of mind brain regions.

Aligning with the bulk of the behavioural results, as reported in Social Neuroscience in 2017 by Liane Young, Emily Wasserman and I, reciprocity and charity both robustly recruited brain regions for theory of mind (including precuneus, dorsal and ventral medial prefrontal cortex), relative to impartiality and the control condition. As might be expected, given how people considered reciprocity- and charity-based allocations to be more motivated by the circumstances of beneficiaries than impartial allocations, participants evaluating allocators in these conditions displayed significantly more brain activity indicative of processing of allocators’ mental states.

With a window into the neural processing involved in the moral evaluation of allocators we saw beyond pre-existing characterisations of forms of fairness and observed how they manifested in social cognitive processing regions in the brain. In this way, we were able to observe that the moral evaluation of two forms of fairness that appear very different on the surface – reciprocity and charity – both recruited robust theory of mind brain activity. Impartiality, by contrast, was rated optimally fair, just as morally praiseworthy as charity, and recruited far less theory of mind brain activity than both reciprocity and charity during moral evaluation.

What are the implications of these results for how we understand the moral cognition involved in judging these different kinds of fairness? Moral judgement has long been discussed as a process involving thinking about people’s mental states and intentions, yet here we saw something interesting emerge in moral judgement of fairness: the fairest type of fairness was not recruiting much theory of mind at all. Greater activity in the theory of mind brain regions was a cue to people being in one of the conditions of lesser fairness, in which it was harder to judge whether the allocator was “doing the right thing”: reciprocity or charity.

Our investigation suggests that fairness has a prototype: impartiality. These descriptive results do not entail the normative conclusion that impartiality is morally right and good. It does let us infer that when we’re being impartial, it’s a mode of behaving that says a lot about us. Our motivations are revealed: we seem unemotional and grounded in standard procedures, and our judges might be able to morally evaluate us without too much social cognition. (Indeed, perhaps part of the appeal of impartiality is it’s easy on our brains!)

Fairness will continue to mean different things to different people. Certainly, we’ll continue to experience and periodically embody in ourselves discordant mixtures of self-interested Machiavellians, bleeding heart empaths, and coolly rational, impartial agents. Individual differences in Machiavellianism and empathic concern may be worth considering in one’s organisational messaging because they represent potential sources of current controversy. However, impartiality – which does not trigger neural activity for social cognition and theory of mind to the extent that “person-based” allocations including reciprocity and charity do – is likely to strike most affected people as fair. It’s rated as optimally fair, highly moral. Additionally, it is perceived as more motivated by the interests of the group, not unique individuals, and by standard procedures, not the allocator’s emotions.

This doesn’t mean that we must be uncharitable to people’s needs. Fairness comes in more than one flavour. These flavours may be more or less appetising to people in different contexts, but some have wider appeal. For example, in a population of Empaths, needs-based allocation may be fairness-relevant in a way that just isn’t so in a population of Machiavellians. Appeals to impartiality, rather than attempts to spur allocation to the needy by invoking empathy for their suffering, might have the potential to help alleviate disparities more broadly. There is new territory to be mapped that better traces the relationships between people, their interpretation of morally-relevant language, and the actual allocation of resources. The increased understanding that results may help us build something closer to a fairer world – in more people’s eyes.