As a rule, it’s nice when we can all agree. But it’s probably an exception to the rule when we agree only that something has gone very wrong. More (but not much more) precisely, we all agree that something is wrong with how we come to know things, how we share what we know with one another, and how our knowledge informs our actions. Somehow, something is wearing at the ties that bind what we do, say, and think to reality.

Of course, different people explain the looming epistemic crisis differently. But one description has cropped up again and again in the last few years: the idea of a post-truth world.

What does it mean to say that the world is “post-truth”? You might think it describes a situation in which people no longer care about the truth. But if we’re being charitable, that can’t be right. To think that such-and-such is true is very nearly, or just is, to think that such-and-such. At least, if you care whether anything is the case, you care whether it’s truethat it’s the case. If I think that 2 + 2 = 4, I think that it’s true that 2 + 2 = 4. If I care whether the Yankees beat the Mets, I care whether it’s true that the Yankees beat the Mets. So people care about the truth if they care about anything at all.

The Oxford Dictionaries’ definition is more useful. “Post-truth”, they write, means “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” But “post-truth” is supposed to characterise something new, and it’s doubtful that there’s anything especially new about circumstances in which public opinion is shaped primarily by appeals to emotion and personal belief. In any case, if people are afraid that we live in an increasingly post-truth world, it would be nice to know what (perceived) trends give rise to that fear.

I can think of at least ten:

- Declining public trust in legitimate authority or expertise

- Declining knowledge about matters of public importance

- Diminishing roles for legitimate expertise in political decision-making

- Diminishing likelihood that political decision-making is guided by true beliefs about the subject matter of the decision

- Declining reasoning skills about matters of public importance

- Declining interest in civil debate or discussion

- Increasingly expressive or performative (and decreasingly assertoric) public discourse

- The increasing confinement of public discourse to echo chambers and filter bubbles

- The rise of fake news – deliberate disinformation spread by purported news outlets

- Declining journalistic standards

To be clear, I’m not sure how many of these trends are real. (In the U.S., at least, there’s some evidence that we trust scientists as much as ever. Educational attainment, which is a plausible proxy for civic knowledge, has increased dramatically in recent years. Trust in the media is unusually low, but I don’t think that journalism today is as careless, sensationalistic, and nakedly partisan as it was in the nineteenth century.) To the extent that these problems are real, though, they’re largely going to be solved through politics and public education. Philosophy won’t solve them all by itself.

But we shouldn’t be too modest. Philosophy has a role to play here. In particular, I’d like to explore three philosophical ideas that, if we took them to heart, would do a little bit to lift us out of our epistemic crisis.

Selective skepticism is a form of credulity

To be selectively skeptical is to raise extraordinary doubts about, or place an unusual burden of proof on, certain sorts of claims and not others. (This should be distinguished from raising extraordinary doubts or demanding unusual forms of evidence in some contexts and not others. We all let things slide in casual conversation that we wouldn’t abide in, say, a courtroom or a scholarly paper – nothing wrong with that.) People sometimes think of all forms of skepticism, including selective skepticism, as reasonable, cautious habits.

But this is false, for two reasons. First, unless we apply a higher standard of evidence uniformly across the board, selective skepticism will tend to favour the acceptance of certain positions. Suppose you demand that everyone who disagrees with you on the internet proves they aren’t a bot before you take what they say seriously, but you take people who agree with you at their word. It’s clear what will happen in the long run – you will become that much more entrenched in your prior beliefs. “Deniers and other ideologues routinely embrace an obscenely high standard of doubt toward facts that they don’t want to believe,” Lee McIntyre writes in Post-Truth, “alongside complete credulity toward any facts that fit with their agenda.”

Second, if you’re thinking coherently, lowering your credence in one proposition means increasing your credence in its negation. Any skeptical doubt comes with a corresponding boost in your belief in something else. William James famously distinguished the “two separable laws”: “We must know truth, and we must avoid error.” But the laws aren’t entirely unrelated. It’s not just that an excessive concern for avoiding error will prevent us from picking up on important truths. It’s that when we hedge our bets on the truth, we raise our stake in error, and vice versa.

Some biases are good

We can think of a bias as a disposition to draw certain sorts of inferences and discount others in ways that aren’t rationally required of anyone reasoning with the evidence available to you. Some biases, so conceived, are bad – prejudicially excessive or deficient credibility in others’ testimony, for example.

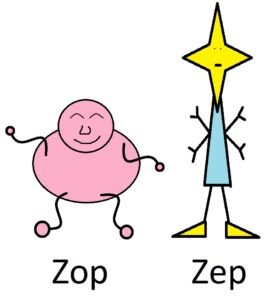

But as the philosopher Louise Antony has argued, other biases are necessary components of a typical healthy human life. This is maybe most obvious in the case of language learning. Allow me to teach you a couple of new words. Here’s a zop and a zep. What do you know about zops and zeps? Let me guess: zops are short and round, with spaghetti limbs and a cheery attitude; zeps are tall, skinny, and angular, with four arms. Or something like that.

Just kidding! Zops are things on the left-hand side of a picture, and zeps are things on the right. Just kidding! Zops are pink things and zeps are blue and yellow things. Just kidding! Zops are things that are smiling and zeps are things that aren’t. Just kidding! Etc.

You ignored these possibilities (and countless others) because you are biased against certain interpretations of novel words and biased in favour of others. But that’s a good thing! It would be impossible to learn a language without these biases. Other examples of “single case induction”, (which are often dependent more on learned background knowledge than our innate capacity for language learning) would show something similar – biases can help us ignore unhelpful or irrelevant possibilities in order to figure things out more quickly, without wasting our scarce investigative resources.

Maybe it’s a bit too simplistic to say that biases are good whenever they help us reach the truth more efficiently or help us understand one another. (Or maybe not.) At least these are some ways that biases can be good. This is worth bearing in mind the next time you hear someone accuse another person, or some knowledge-sharing institution, of bias.

A plea for better media criticism

An outsized quantity of popular media criticism in recent years has revolved around the problem of fake news and the question of journalistic objectivity. Both of these focuses seem mistaken to me.

Objectivity first. Part of the problem is that the discussion of objectivity in this context seems to follow a weirdly anti-realist script – either excessively shy (in a way that doesn’t fit our ordinary claim-making behaviour) about what is and isn’t true, or unnecessarily committed to the view that there is no mind-independent truth about the news. But even if we didn’t follow this script, it’s clear that “objectivity” means very different things to different people. When we say that someone is making an objective judgement or speaking objectively, we might mean, perhaps among other things, that:

- they’re not expressing a value judgement or an emotion

- their judgement isn’t biased

- they don’t have a stake in the matter

- they’re reasoning in a way that any reasonable person would accept

This ambiguity makes the discussion of objectivity needlessly messy. These different varieties of objectivity are, at best, loosely correlated with each other. But messiness aside, a little reflection shows that none of these varieties of objectivity is desirable in all circumstances. Sometimes values and emotions cloud our judgement, but sometimes they help us get closer to the truth or are useful for other reasons. Sometimes we want to hear from impartial judges, but sometimes we want to hear from people with skin in the game. How we reason with the information we have is very generally dependent on what we already believe, but there’s nothing wrong with that (to a first approximation) if there’s nothing wrong with what we already believe.

As for fake news, we might subscribe to the philosopher David Coady’s argument that the concept (along with the concept of a conspiracy theory and the concept of post-truth itself) exists only to help the powerful exclude inconvenient ideas from public discussion. But we don’t need to go that far. If we take fake news to be intentional disinformation spread by purported news outlets, people just don’t share fake news very much. One widely cited 2019 paper in Science Advances found that over 90% of the Facebook users in their sample didn’t share any fake news in the year 2016. And even if someone does share a piece of fake news, a number of simple media literacy curricula show that it’s not that hard to teach people (kids, even!) to spot it. (Of course, if we define “fake news” more broadly, so that it includes all misleading news, it will constitute a serious problem.)

I suspect we focus on fake news as much as we do in part because of our generally reactive relationship to the news and in part because we don’t have a rich enough vocabulary for describing failures of the press. These two problems go hand in hand – if we had a relatively stable, explicit sense of what we want from the press, it would be easier to distinguish serious problems from the sorts of overheated panics to which public discourse is prone. So I’ll end with a positive suggestion about three more fruitful directions for future media criticism: coverage priorities, funding models, and credulous reporting of government sources.

The criteria journalists use to evaluate the newsworthiness of stories are largely implicit, which makes them difficult to criticise. But media scholars have long noticed skews and imbalances in news coverage that are hard to justify. As Herman and Chomsky observed in their classic Manufacturing Consent,the U.S. press tends to cover unflattering news about hostile foreign nations more than unflattering news about U.S. client states. They compared the coverage of the murder of a single Polish priest by agents connected to the Soviet Union with coverage of a number of massacres (including a massacre of U.S. missionaries) and one murder of a priest in U.S.-allied countries in Latin America. At each news outlet in their sample, there were more stories about the Polish priest than about all the other violence combined. We might ask, to similar effect, about horse-race election coverage at the expense of coverage of the issues, coverage of particular events at the expense of trends or explanations of on-going states of affairs, and coverage of national politics at the expense of state and local politics. It’s an interesting and difficult philosophical question what makes a story more or less newsworthy, which I won’t try to answer here. Suffice it to say that we can make some headway on it by asking what makes these patterns of coverage strike (many of) us as problematic.

Of course, how news outlets spend their editorial resources is partly a matter of their epistemic values, but largely a matter of financial necessity. The press is perhaps unique among other institutions in that it is both necessary to the practice of democracy and, in many countries, completely beholden to the whims of the market. As Masha Gessen argued on a recent episode of the Throughline podcast:

“we have something that we think of … as essential to democracy, as being the fourth branch of government … And then we leave it to profit-making corporations that are entirely what we call self-regulated, which is another way of saying unregulated, right? And then we’re surprised when we get really bad results because they’re functioning in accordance with their incentives and not with the incentives of democracy. I mean, we don’t tell Congress to rent out rooms in the Capitol to sustain its business of making legislation. We fund the courts and pay judges’ salaries and make clear sets of rules by which the courts function…

“And then there’s … this idea that it can’t possibly be government-funded, it can’t possibly be regulated, or else it will be an infringement on freedom of speech. But I would much rather negotiate the terms of existence of the media with other Americans and hold the people who are enforcing those terms accountable through electoral and other institutional mechanisms than not have any terms.”

The press’s dubious implicit coverage priorities and tenuous funding are both related, in turn, to the press’s relationship to government sources. Journalists are often dependent on (and tacitly committed to the newsworthiness of) government press releases, public statements, and unattributed leaks about a number of topics. The most spectacularly disastrous consequences of this dependence were evident in the months leading up to the Iraq War, when journalists’ reports from anonymous sources about weapons of mass destruction were later cited as evidence in public statements from the sources themselves. The recent resurgence of the Movement for Black Lives has also called attention to the practice of reporting local police departments’ (often false, generally exculpatory) claims about their own officers’ conduct without criticism or comment. Would it be too much to ask that unverified claims by the police are always explicitly described as such? Would it be too much to ask that unverified claims by the police aren’t printed at all?

Perhaps this will all seem like bad news for philosophers. After all, objectivity, fake news, even the concept of post-truth – all of these things are manifestly in our wheelhouse. What is there for us to do, if the real problems with the press lie elsewhere? But at this point, I hope the answer is clear. Even if we agree that we should be talking more about coverage, funding, and sourcing, there are a lot of really important questions here about free speech, what democracy requires, how we handle untrustworthy testimony, and the nature of newsworthiness. Let’s get to work.